Saturday, December 30

Empty handed

It may or may not be interesting to note that until just recently I had always been more of a Borders man than a Barnes & Noble man. Borders, as you may know, began in Ann Arbor, and the flagship store on East Liberty really is quite marvelous. When I lived in Boston I used to go out of my way to shop at the Borders by Downtown Crossing even though I lived nearby the BU Barnes & Noble as well as the Prudential Center Barnes & Noble. Just one of those silly quirks of brand loyalty I suppose. But here in Seattle I quite prefer the downtown Barnes & Noble to the downtown Borders (Borders still reigns supreme in the music and DVD departments, but this is Book-Loop, where such ephemera are cast aside in favor of more scholarly pursuits). Perhaps as my college days grow more distant my bond with Borders slowly crumbles. Or perhaps it is simply the case that the Barnes & Noble is more comfortable, their staff far less intrusive as I browse, their patrons far more convivial. Granted, neither of these nationwide behemoths can hold a candle to the local gem that is Elliott Bay Book Company, and so this entire paragraph becomes obsolete.

Because of my allegiance to Elliott Bay it probably comes as no surprise that my Barnes & Noble gift certificate, while received with much appreciation, has caused me some frustration. I stroll through the aisles at Barnes & Noble in search of books I know to be plentiful at Elliott Bay and I come away wanting. No Davies, no Cheever, no Percy, no Marcus. Why, not even Catch-22 or The Brothers Karamazov, two classics that seem to have unforgivably slipped through the cracks of their shelves and mine. At one point I held Richard Ford's The Sportswriter in my hand. I put it back to browse some more and when I returned some time later, deciding that at the very least I could get that for now, it was nowhere to be found. I stormed out, no books in hand. Sure, I'll give them the benefit of the doubt, the holidays scurried away leaving the literature section in something of a drought. Hopefully a restock is in order, or I'll have to shift back to Borders.

But seriously, I did stumble across a Colson Whitehead book of essays regarding New York titled, The Colossus of New York. Not sure if either Bryan or Louis have read this, but seeing as how Bryan is now unashamed to refer to himself as a "New Yorker" I figured this might be of interest. I read the introduction and skimmed (it's true!) through other portions with great delight. If I, who has passsed through New York only a handful of times, find the book of interest, I thought others here might feel even more strongly about it.

Also stumbled across a book called 1001 Books to Read Before You Die, or some such foolishness. It seemed decent. But really, is every novel by Ian McEwan and Don DeLillo worthy of being placed in a top 1001? 1001 isn't really a lot when you consider the list begins circa 600 BC with Aesop's Fables.

Wednesday, December 27

A good haul

Books now in my possession:

Sixty Stories - Donald Barthelme

The Stories of John Cheever - John Cheever

CivilWarLand in Bad Decline - George Saunders

The Areas of My Expertise - John Hodgman

The Paris Review Ineterviews, Volume I

The Better of McSweeney's, Volume 1

Books for Mom:

We Tell Ourselves Stories in Order to Live - Joan Didion

Brick Lane - Monica Ali

The Echo Maker - Richard Powers

Books for Dad:

A Madman Dreams of Turing Machines - Janna Levin

The Geographer's Library - Jon Fasman

Waiting for the Barbarians - J.M. Coetzee

The History of the Siege of Lisbon - Jose Saramago

Yiddish with George and Laura - Ellis Weiner and Barbara Davilman

Books for Brother:

The Best American Nonrequired Reading 2006

A Fictional History of the United States (with Huge Chunks Missing)

100 Hikes in the Inland Northwest

What books did you all get? Louis, you get anything good?

Saturday, December 2

Books for the non-reader

This year I have been giving much thought to what novels I might be able to give him that won't go unread. I have considered The Gunslinger, the first volume of Stephen King's Dark Tower series. People seem to like, but who knows, the only King book I have read is The Shining, an altogether different affair. Then there is Neal Gaiman's American Gods, a fairly literary novel with enough fantasy that its length might prove to be a non-issue. Also, I have considered Benjamin Kunkel's Indecision, a humorous debut novel about a twenty-eight year-old slacker who takes a drug that cures his chronic indecision and soon finds himself romping about South America. While my brother might greet the humor and subject matter in Indecision warmly, I want not to have him think I am sending him some sort of not-so-veiled message about his own life--which would not be the case--so I have shied away from this one temporarily.

But, in general, what are some good books for the non-reader? Off the top of my head there are some obvious non-fictions like the work of Klosterman and Sedaris--breezy, fun books that seem to appeal to the well-read and unread alike. I struggle a bit more when trying to generate a list of novels. Perhaps this is because I am an elitist when it comes to the book gifts. Indeed, King seems rather too populist for my gift-giving sensibility. Something like Life of Pi is a swell choice, I think. And, while some skimmers might disagree, I believe the shorter novels of Murakami are a fine selection for a person such as my brother with an apparent taste for fantasy but an aversion to literature.

I could ramble on longer, but I come to you now from the communal computer in my apartment building and folks are waiting. If they only knew how urgent this Book-Loop correspondence was they would go upstairs, take a nap and give me more time, but no, they seem quite impatient.

Monday, November 6

Let's talk periodicals

Two Book-Loop members who are not active contributors have expressed that they cherish their periodicals so much they have not the time for book reading. It's perfectly understandable. I now find myself in a situation with a new job and a plethora of magazine subscriptions (most of which came my way through gifts and free offers) and I worry that book time might be lacking. The larger issue facing me is that amongst my numerous periodical subscriptions there are only a few that I consider essential reading. I will probably subscribe to The Believer, The New Yorker and Sports Illustrated for the remainder of my life. Dime, ESPN The Magazine and Stuff are dying slow deaths. URB, Esquire, Wired, Time Entertainment Weekly are not likely to be renewed beyond their current run. Playboy is in limbo as well. The Economist is a new kid on the block and I look forward to the start of the free one year subscription I received in exchange for 900 or so Delta Sky Miles. The Paris Review and The Atlantic I enjoy reading, but I am not a subscriber. I think I'm saving those for my wizened, fireside-sitting, pipe-smoking years, which I plan to dive into somewhere in my mid-thirties.

What periodicals do you read? What periodicals do you recommend? What periodicals would you read if you had more time? What's the word on Mother Jones? I spent some time checking out the magnificent magazine collection at Elliott Bay this afternoon--a swell way to kill a rainy day while waiting on Pats/Colts--and was quite overwhelmed. I realize that the best way to find magazines you like is by reading magazines for yourself, but with so many hundreds of magazines out there I figured it would be neat to open up a little dialogue about the wonderful world of periodicals. I'm here to listen.

Friday, November 3

Friday, October 27

Pastoralia Ramblings

Listen to Saunders on The Sound of Young America (Begins at 22:05)

I have also been continuing my journey through the drug-, ego-, and testosterone-fueled history of 1970's American film in Easy Riders, Raging Bulls. A little too gossipy for my tastes but a damn fun read. I wish I'd been making notes along the way because there are just too many great anecdotes to recount. One of my favorites involves the strategic drug use of the bat shit insane Dennis Hopper:

One director wouldn't use him after lunch, when the alcohol kicked in. Another knew that Dennis would grab whatever was around--uppers, downers, what have you--and worried that, say, if Dennis took one drug during a long shot in the morning and a different one during a close-up in the afternoon, the energy levels would be different, making it impossible to cut them together. The two men went through the script and agreed on what drug Dennis would use in each of his scenes. When Hopper got the next day's call sheet, there was a notation at the bottom indicating the appropriate drug.I suppose this tidbit is of particular interest to me because it perfectly illustrates how, while the era is remembered for its freewheeling approach and active abandonment of Old Hollywood techniques, the people involved in these pictures were quite serious about their craft. I suppose that's obvious, you don't produce several of the greatest works in the history of film by simply ingesting drugs and letting the cameras role, but it's one of the major points that I take away from the book. Well, that and the understanding of how, like with so many great writers and musicians, the ego and ambition that fueled the work of, say, Peter Bogdanovich and Bob Rafelson, created relationships with friends and lovers that were tumultuous at best. They were endlessly philandering, self-absorbed and destructive. Indeed, it sometimes seems as though these traits are mandatory for achieving greatness in the arts.

So how might this relate to the previous Book-Loop discussion regarding the acquisition of a writer's sometimes upsetting biographical details. Perhaps it's instructive that my new understanding of the salacious details of these filmmaker's private and professional lives has done little to weaken my appreciation of their work. If anything, reading the book has probably enhanced my appreciation of the films. My perception of Hollywood is that it's a seedy place--always has been. I expect bacchanalian excess and dirty double crossing. Not only do I expect it, but I think it adds to the legend and might even be an essential part of America's (dwindling) love affair with motion pictures. The written word is very different. Filmmaking is a group affair, vulnerable to in fighting, abuses of power and mutiny. Writing is a solitary act, it is personal. Why I place writers on a higher moral plane I cannot really say. I think it's mostly affect, but maybe it also comes from the (false?) idea that writing comes from the soul while movie making is one big put on--actors, costumes, make-up, sets, special effects, etc.--and even when it's a personal tale or a so-called auteur picture it lacks the one-on-one interaction that a book offers.

Ah, this post is a rambling mess. I seem to ramble much more on this blog than I do on my own. I'm not sure why, but I like it.

Friday, October 20

Winning excerpts

"[Bob Rafelson] was handsome in the Jewish way, a shock of dark brown hair over a high forehead, rosebud lips frozen in a permanent pout under a fighter's battered nose." - Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-and Rock 'N' Roll Generation Saved Hollywood

Wednesday, October 11

Up from the ashes

After breakfast I made my way to Elliott Bay Book Co. to do some browsing. I read the preface to Natural capitalism and very nearly bought it before having one of those little internal meltdowns where you decide that you must get out of the store as soon as possible because you simply do not possess the resources to procure even a single book, and if you stay much longer you will almost certainly wind up exiting the store with five. So I put it back and made my way to the door. A little book titled "Speech of Chief Sealth" caught my eye and I stopped to give its innards a once over. An elder lady crept up alongside me and leafed through a different Native American non-fiction. She wandered off just as four books indiscreetly tumbled from the shelf and onto the rustic wooden floor. I quickly made an effort to shepherd the lost books back to where they would be more comfortable. Once I had placed the books back neatly on the self the lady, offering a reaction sufficiently delayed so as to suggest an incertitude of cuplability where there truly was none, asked "Did I do that?" I responded, "Oh, no, I'm fairly certain it was gravity." I gave her a wry smile and once again made my way to the exit. Netted in once again, this time by an autographed copy of Michael Lewis's latest book, The Blind Side, my departure was delayed further. I soon spotted Feeding the Monster, which, were I of sound mind when it was released a few months back, I would have surely bought it the very day it came out. So I bought it.

Walking home I passed a smiley faced man handing out reading material on the street. 'Jesus Saves!' 'Go Vegetarian!' 'No on I-933!' I was not sure what he was distributing but I accepted his offering graciously. I made an attempt to read it. I could not. It was a blank sheet of white paper. All his papers were blank. The man is a genius! I went into a shopping center where I sat and read the introduction to Feeding the Monster. Upon leaving I passed the man again but declined his handout, telling him, "No thanks, I've already read it."

Friday, September 29

Recent Perusals

A Good Man is Hard to Find and Other Stories - Flannery O'Connor

Sixty Stories - Donald Barthelme

Collected Stories - Isaac Babel

Selected Short Stories - Honoré de Balzac

Of the four I have to this point only completed a significant sample of O'Connor and Barthelme. This is my first experience reading either writer. "Grotesque" is the word that comes up again and again in discussion of O'Connor's work. Her stories are matter-of-fact and menacing in their portrayals of salvation. I am glad to be acquainted with her, and in awe of her ability to be so harmoniously dire and comedic. Barthelme is a writer of whom I could see the Book-Loop clan holding a mixed opinion. To me the man is downright brilliant. His short stories are brief, their relative simplicity belying an ingenuity of form. Why must "Postmodernist" be a pejorative label? But aside from the merits of his experimental style, Barthelme's stories are witty and far more playful in demeanor than the existentialists he is often lumped with. If a reader cannot delight in reading "Me and Miss Mandible" they should probably begin searching for a new hobby.

And yes, I am reading some non-fiction. On Mike's recommendation I picked up The Unfolding of Language: An Evolutionary Tour Of Mankind's Greatest Invention at the library. Pretty self-explanatory from the title, and, let me tell ya, the story is more interesting than you might imagine and the writing is far less stilted than you might fear. I also got a dense looking tome called The History of the English Language, an acquisition made with much optimism that shall probably return to the library unread.

Also:

The Office's John Krasinski adapting David Foster Wallace story

Reimagining Madame Bovary 150 years after her birth

The Wanderer: The Last American Slave Ship

Can Men Write Romantic Novels?

Housekeeping vs. The Dirt, by Nick Hornby

Tuesday, September 26

Joe Mathlete Explains Today's Marmaduke

Joe Mathlete Explains Today's Marmaduke

Monday, September 25

Bah!

Thursday, September 14

Regarding Jack London

Writing in the New York Times Book Review, E. L. Doctorow pronounced London "the most widely read American author in the world." That's right. More than Twain or Hemingway or Melville. Something of a literary footnote in his own country, Jack London is considered an emblematic American author in Japan, Russia, Eastern Europe, and elsewhere. The Call of the Wild has been translated into eighty languages, more than any other American work. An Albanian anthology of American literature pictures Jack London along with Mark Twain on its cover. A collection of London stories in Russian sold 200,000 copies in the first printing. On his deathbed, Lenin asked his wife to read him a Jack London story.Who knew? Also, this man who readers of our generation (if they're anything like myself) know only from Call of the Wild, White Fang and perhaps To Build a Fire, wrote more than fifty books! This is a swell article that offers insight into a life that some would call "as romatic and ruggedly American as any novel ever written." We also encounter a rather comedic fellow who is a part-time Jack London impersonator, part-time hardware store manager.

H.L. Mencken, master of the hedged compliment, on London:

I have often argued that he was one of the few American authors who really knew how to write. The difficulty with him was that he was an ignorant and credulous man. His lack of culture caused him to embrace all sorts of socialistic bosh, and whenever he put it into his stories, he ruined them. But when he set out to tell a simple tale, he always told it superbly.

Spade Swann Bloom

I have also been hopping around Harold Bloom's Genius. It is a fun book in its own way. The manner in which Bloom has grouped the 100 writers and thinkers together into lustres makes the book easily navigable for someone like me who opts not to read all 814 pages in succession. The entries on each individual are brief, some of them providing an overview, others focusing on more specific qualities that Bloom finds most interesting. I have read so few of the works discussed in this book, but even without an intimate appreciation for many of the writers I am thoroughly enjoying the way in which Bloom makes connections between them, shaping in my mind a sort of outline for a family tree of poets, playwrights and authors. Inevitably it is Shakespeare who pops up again and again, but not always. Like the Book of Writers Talking to Writers, Genius is a book I will revisit often, whether it be for inspiration, edification or simple pleasure.

Wednesday, September 13

Quoting Davies

"The great book for you is the book that has the most to say to you at the moment when you are reading. I do not mean the book that is most instructive, but the book that feeds your spirit. And that depends on your age, your experience, your psychological and spiritual need."

Tuesday, September 12

Old School

These visits represent the source of much of the book's drama. Each visit corresponds with a school-wide contest in which the visiting writer selects one student's work to be read aloud and published in the school's literary journal. Most important for the students, of course, is the fact that these legendary writers would be selecting them as the winner--in their minds paving the way for an inevitable life of literary fame. The Frost visit is humorous, as he selects a student's work that he believes is a clever parody of his own poetry. He accepts the piece as good-natured ribbing, even though the student's intention had been only to write something Frost would find beautiful.

Rand also selects a student's work in which she is able only to see herself. But the contest takes on a secondary importance, as Rand's speaking engagement destroys our protagonist's enjoyment of her work. Like many young scholars he reads The Fountainhead and becomes enthralled with Howard Roark's boldness and virtuosity. Then, in this case from Rand herself, he learns what the writer really had in mind and the idolatry quickly vanishes. I strongly recommend the Rand section for anyone who still clings to the misguided belief that her philosophy is worth a damn. Wolff's characterization of Rand is hilarious, and even if it is a little harsh I would say that it is fully deserved.

The climax of the tale coincides with the approach of Hemingway's visit. Some of the students pretend to dismiss Hemingway, but none of them are able to avoid ripping off his style. In an effort to channel Ernest's ability our aspiring writer takes up the practice of re-typing Hemingway's short stories. The strategy works, in a sense, but the outcome is not quite what the young lad had in mind--the fact that the story ends up being a little more like F. Scott than Ernest is the least of his concerns.

As for complaints, I shall now turn you over to Thomas Mallon of The Atlantic, who has captured my two central points quite crisply:

Old School's somewhat pedagogical nature inclines one toward a few schoolmasterish objections. Its gradual accrual (three episodes from it appeared in The New Yorker) may have lulled the author into writing a last chapter that, although a rattling good story, seems more like an appendage than a conclusion.... And let me say this, above all, Mr. Wolff: the lack of quotation marks around the dialogue is a ridiculous piece of postmodern pretentiousness that has no place in your book. Not when it can stand with the best of what some old boys (Louis Auchincloss, Richard Yates) have produced in a waning American genre.

Saturday, September 9

Thursday, September 7

The Great American Novel

I give it three PLDS games out of five.

Tuesday, September 5

Peak Oil

So far on Book-Loop it appears that the prevailing winds blow toward fiction. That's fine, but I am caught in a non-fiction spell that goes back 4 or 5 books or so and shows no obvious signs of letting up (the books at my bedside are What's the Matter with Kansas?, James Beard's Theory & Practice of Good Cooking, and The Joy of Sex, which I suppose you could consider fiction depending on the circumstances of the moment.

My question is, does anyone have any plans for non-fiction in the near future? If so, I would suggest a book on Peak Oil (which is exactly what it sounds like - the final peak in oil production. Ever.). I have not yet read a Peak Oil book, but I would like to. I was confronted most recently with the subject while reading an article in Harper's. Apparently, there is a lively Peak Oil community in the United States and I would assume around the globe. Peak Oil is not simply an inevitable event in the future, it is a movement of the present, populated by thinkers, crazies, scholars, business persons, and, well, anyone who has the ability to think critically about the consequences of a powerful, charging pattern of digging, pumping and burning that could competently serve as a shorthand for the recent history of human behavior.

This Harper's article included predictions, or rather meditations, of what life would become on an earth at Peak Oil, or on the immediate come-down. LTS mentioned thought experiments a while back. The thought experiment, or imagination experiment, of considering a realistic vision of an oil-dry planet is an intriguing exercise that probably is not undertaken enough outside the open discussion of a meeting of Peak Oilers. The scenarios are of course infinite, but some simple questions can be shocking if considered honestly.

What sort of war might we see over the last large deposit of oil on Earth? What might happen to our society if the price of gas rose to ten dollars per gallon over a period of ten years? The funny thing about thinking about this issue is that the only "what if?" in the scenario is the way in which the events of the peak and decline of oil production will occur. That they will occur is a plain fact.

Has short-sightedness always been a quality of the masses of humanity? I would think that the rapid pace of millennial (where are we, modern? Post-modern? I don't know these things) society would cause us to look ever farther into the distance since the consequences come at us faster and we will actually be around another 60 years or so to live more of them, supposedly. But, as a general observation, I feel that we are more short-sighted than ever in our hunger for progress.

Saturday, September 2

Happy Days

Friday, September 1

Dumbass

Monday, August 28

Translation

I have an old, used copy of Swann's Way that I have been thinking about reading. The other day I was in the book store when I noticed that each volume of Proust's In Search of Lost Time is now available in a new translation. Not only a new translation, an award-winning translation that has received robust praise for numerous sources. The little staff recommendation note hanging below the new Swann's Way dismissed my poor old copy as anachronistic. I ventured to the library in the hope that I would find the updated version in their collection. Alas, their volumes of Proust are even more elderly than my own.

I suppose now is the time to ask, Has anyone read any Proust? Was it the updated translation or the 1922 translation? What did you think?

According to the blurbs, updated translations usually offer things like new life and improved fluidity of prose and access to subtle humor. For example, the 1996 translation of Magic Mountain is supposed to read far more easily than its predecessors, improving on their "stiff and forbidding" language.

The effectiveness of a translation is something that is apt to bother me so much while I am reading a book that I'll attempt to expel it from my thoughts and just pretend that it was originally written in English. But it's a HUGE factor for any book that one reads in translation. Thankfully most translators are amazingly talented. Any good writer will say that each and every word within all of their stories has been meticulously selected. Every word that sits on the page sits their actively, with purpose, they do not reside simply to fill some quota. To take each of the words, and the strings of words that they produce, and bring them into a new language is nearly as meticulous as writing the book in the first place. I just don't know how they do it. Bravo, translators.

Has anyone had an experience where they read a book they simply could not make it through, only to find themselves reading a different translation of that same book later on and enjoying it? My hunch is that many of the differences would be too subtle to swing one's appreciation so wildly from one pole to the other. As an amateur in the world of letters I would guess that updated translations are best suited for those who wish to expand an existing appreciation for a work. But odds are I am wrong. In fact, I know I am wrong. So wrong that I don't think I'll ever read my 1922 translation of Swann's Way. If a better translation exists, why bother?

Another thought, Why are the new translations always found in super deluxe editions? Yeah, the words are new, but why must that require paper of the highest quality and snazzy design work? Damn publishers.

Friday, August 25

What makes a book good?

My responses intrigued me. For instance, I saw The Effect of Living Backwards by Heidi Julavits, a book I did not enjoy while I read it - but its themes are burnt into my head. I also saw two David Sedaris books, Naked and Me Talk Pretty One Day, books I remember loving, but I can't recall a single episode from either of them. Sedaris may be a bad example, because his writing is purposely disposable, but what to make of Julavits? My experience with her book is almost the opposite of what I'm going through now with The Great American Novel. For whatever reason, I'm kind of having a rough go with it, but I only have good things to say about it, whereas I plowed through TEOLB despite my disdain for a lot of what was going on. The tricky part is that I remember a lot of it, and I would say it's a good book if you want to see the effects of shame. In some ways, it's kind of like Anchorman. I like quoting Anchorman, but I've never found it particularly funny when I watch it. That's obviously a strike against it, but with its sticking power, how big of a strike is it?

Wednesday, August 23

Do you like to know your authors?

It was only after I had read a fair amount of Saul Bellow's work that I began to make an effort to learn something about his life. Even then, my interest was prompted by a friend who had some less than glowing appraisals of Bellow the human being. My inquiry revealed that Bellow had a reputation as a misogynist, a bit of a racist and a part-time neoconservative with a distate for counter-culture. Disappointing revelations indeed, but with my fondness for Bellow's writing already well-established, I have been able to navigate around these unfortunate bits of information and separate the man from his fiction.

I remember distincly an incident when things did not work out quite so neatly. It was during my tenure at an educational software company in Boston. I was on my lunch break, eating lunch in the office break room. I was sitting there, munching on carrots, reading Spring Snow, when the rude and annoying project manager with outrageous halitosis joined me at the table. She noticed my book with some excitement and ventured into a lecture on Yukio Mishima's ritual suicide. When she was through I returned to my desk rather disturbed, and when the work day was done I returned Spring Snow to the library. I wasn't able to separate the man from his fiction because I was not given the opportunity to wander through his writing on my own. I was frustrated by the information I had attained--at least in part because of its source--and so I gave up on the book. I'll get back to it someday soon.

In many cases learning about the life of an artist can enhance one's appreciation for that artist. Unfortunately not all artists are admirable beings, and more than a few have some serious skeletons in their closets--one need not look any farther than the recent news of Günter Grass's secret SS past. Distinguishing the artist from the person behind the art is often easier said than done. I am unsure about what the role of the reader should be in terms of investigating the life of the writer. In most cases I try to avoid the biographical details altogether, but part of me thinks that it is the obligation of the discerning reader to dig into the details and attempt to find out what it is that makes a writer tick.

Discuss.

Sunday, August 20

The Intuitionist

The grand metaphorical relationship between elevator and upward racial progress is initially rather obvious. However, as the story develops this metaphor becomes cumbersome and difficult to uncurl. The fact that it is omnipresent throughout the tale does not help matters much. But rather than getting bogged down with my struggles to interpret Whitehead’s Big Idea, I delighted in becoming acquainted with some of the smaller aspects of the story.

Particularly fascinating to me was the character Pompey. It is Pompey, the only other black member of the Department of Elevator Inspectors, who Lila Mae blames for being directly responsible for her setup. She thinks him an Uncle Tom and is suspicious of him from the start. The lone black figures in the office are adversarial and impersonal rather than partners on the rise up.

I enjoyed the way in which Lila Mae slips into the party of co-workers undetected simply by wearing a maid costume. Her drunken co-workers, probably more than willing to look right through her anyway, do not notice Lila Mae at all in her simple disguise. Whitehead underlines the alienation of Lila Mae perfectly in this segment.

Also of interest is the fact that the most successful black character in the tale, James Fulton, had the ability to pass as a white man. I point it out because this idea is the central focus of two celebrated novels in the African-American literary canon that I highly recommend, James Weldon Johnson’s The Autobiography of an Ex-Coloured Man and Nella Larsen’s Passing.

The one major gripe I have with the book is the fact that Lila Mae is as cardboard a character as I have come across in some time--though I'd be willing to entertain the idea that this was intentional. I consider it rather adventurous for a young man to pen his first novel with a female character as the central figure. I know some writers who would find this opinion laughable, but I think it takes a special talent to pull it off. Now, obviously Whitehead is an immensely skilled and witty writer, extraordinary sentences abound throughout The Intuitionist. I only wish he were as generous with Lila Mae’s characterization as he is with his prose.

Bryan, you mentioned that I wouldn’t believe what you were doing when you read this book. Were you investigating an elevator catastrophe cover-up for the Queens Chronicle? Do tell.

This book is certainly ripe for discussion. Let us proceed.

Saturday, August 19

A book-loop suggestion

I think it's at least worth a try...

Monday, August 14

Mitchell favorite to land Booker literary prize

Here is the longlist for the Man Booker Prize for Fiction.

Black Swan Green seemed to be met with a cooler reception by British critics than American critics (small sample size, I know) and yet it is now the front runner for the Booker.

Critics who reacted negatively towards Black Swan Green seem to view it as a step back for Mitchell. While it is certainly not as daring as either Cloud Atlas or Ghostwritten in terms of toying with notions of time, setting, reincarnation, etc., or experimenting with interlinked stories featuring disparate narrative voices, it is far from a standard coming-of-age novel. In Black Swan Green we find Mitchell focusing on a very particular moment in time (Cold War England of 1982) a very particular place (Black Swan Green) and a very particular person (Jason Taylor). While not as grandiose as his past efforts, I hardly see this more microscopic focus as a step backwards. Rather, I think one could argue that in abandoning some of his tricks and telling a far more measured tale we see Mitchell maturing and bringing his writing to an even higher level.

One thing I am a little bummed about upon seeing the cover of the Black Swan Green U.K. edition for the first time is the fact that all of Mitchell's novels feature more interesting covers on the U.K. editions. See for yourselves:

U.K. Black Swan Green

U.S. Black Swan Green

U.K. Cloud Atlas

U.S. Cloud Atlas

U.K. Ghostwritten

U.S. Ghostwritten

Now, obviously the cover art is a rather inconsequential matter, but it's interesting to note that Black Swan Green is the first of Mitchell's novels that has not seen the inside of the U.S. version differ significantly from that of the U.K. version. In his first three novels the British terms (boot, lift, chips etc.) and phrases (lord only knows) were edited out and replaced by more commonly American-speak. But with Black Swan Green, as with many coming-of-age tales, the slang and local peculiarities of the town are an essential component to the story, so the words remained unchanged.

Sunday, August 13

Did the novel's ending make him uncomfortable?

Bush reads Camus's 'The Stranger' on ranch vacation

Why is George Bush Reading Camus?

Honey, I Read "The Stranger"!

Saturday, August 12

You think you know a guy...

It was Grass first and foremost who insisted the Germans “come clean” about their history and that his own generation should not try to pose as “victims” of Hitler’s National Socialist ideology. Now the great advocate of facing unpalatable truths has lived up to his own standards, but a little late.I just came across this quote that takes on new light:

"Believing: it means believing in our own lies. And I can say that I am grateful that I got this lesson very early." - Günter Grass

Grass says literary reputation hurt by SS admission

Storm grows over Grass's belated SS confessions

Grass to retain Nobel despite row

John Irving defends author Guenter Grass

Grass' autobiography selling fast amid SS furore

Friday, August 11

Parents and Books

I viewed my mother as the person who kept the house in order, broke up fights between my brother and I, and sometimes snuck off to read escapist mystery stories. Again, this image was not far from reality, but in this case I didn’t seem to take into account the person I thought my mother wanted to be—I had no idea what she wanted to be, my view of her was too narrow. My mother struggled to work books into her busy schedule and opted for quick escapism because that was the best therapy after the many hectic days. My father struggled to work his kids into his busy schedule and opted for classical music and literature as a way to escape from a different sort of reality.

As I’ve mentioned numerous times on my blog, one of the great joys of my maturity has been the discovery that my father and I share similar taste in both films and books. What I have failed to mention is the growing relationship between my mother and I that is based on talking about films and books. While my father and I share a similar fascination with figures like Kafka, Hesse, Bergman and Buñuel, we very rarely, if ever, discuss their work. Meanwhile, my mother and I have shared many enjoyable phone conversations recently about the films I’ve been watching and the books I’ve been reading. I introduced her to David Mitchell’s novels and she’s taken a great interest in them. When I was home around Christmas we had a long discussion about Bergman’s Through a Glass Darkly that I will not soon forget. Just the other day we chatted about Joan Didion.

Through these conversations I have learned a tremendous amount about my mother. It saddens me that it has taken so long for me to connect with my mother in this way. It was always just kind of accepted that my dad was the renaissance dude and we would defer to him on most things cultural. But the fact is that while my father has a tremendous memory for character and plot, he rarely seems willing to share his honest opinion on books. With some coaxing I’ve seen it done, but I’m hardly the person that should be coaxing others to open up. When I read my father’s copies of his favorite books I invariably find several pages bookmarked. I find myself wanting to know why and I try to figure it out on my own. I am rarely able to get inside of his head, and I rarely ask him to let me in.

These days my mother is the literary one and my father is the mystery. My parents haven't changed (at least not in any fundamental way) my approach has changed. I am no longer a simple observer of my parents' images, I am now an active participant in the decoding of those images.

(You know, I’m not sure whether this type of thing is of interest to Book-Loopers. It was sort of caught in-between this blog and the other one so I just deposited it here. I apologize if I have bored you.)

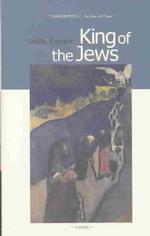

King of the Jews

I just finished King of the Jews by Leslie Epstein (Theo pere). There cover of my copy is littered with praise for the book, most of it calling the novel the only important work of Holocaust fiction to that point. It was published in the early 80's. It was well-written but didn't blow me away; however, it's the best look inside the life of Jews during the Holocaust that I've encountered, as opposed to their deaths (Schindler's List) or their individual fights for survival (The Pianist), even if the fight to survive obviously permeated the book. The surprising aspect of the book is its optimism: the main character, I.C. Trumpelman, refuses to fight the Germans for fear of getting his whole ghetto deported to a death camp, and constantly preaches to his skeptical neighbors that working with the occupiers is better for the Jews in the long run. As President of the local Judenrat, or Jewish Council, in the Balut ghetto, Trumpelman radiates a confidence that doesn't extend to some of the Balut's younger residents, who rebel against him and the Germans; somehow, he holds the Balut together longer than any of the other Polish ghettos. The general optimism was a fresh take, and I think was the reason the book is well-regarded - I enjoyed it for that reason, but couldn't escape the fact that it was obviously certainly fantasy, even if I wished it wasn't.

I just finished King of the Jews by Leslie Epstein (Theo pere). There cover of my copy is littered with praise for the book, most of it calling the novel the only important work of Holocaust fiction to that point. It was published in the early 80's. It was well-written but didn't blow me away; however, it's the best look inside the life of Jews during the Holocaust that I've encountered, as opposed to their deaths (Schindler's List) or their individual fights for survival (The Pianist), even if the fight to survive obviously permeated the book. The surprising aspect of the book is its optimism: the main character, I.C. Trumpelman, refuses to fight the Germans for fear of getting his whole ghetto deported to a death camp, and constantly preaches to his skeptical neighbors that working with the occupiers is better for the Jews in the long run. As President of the local Judenrat, or Jewish Council, in the Balut ghetto, Trumpelman radiates a confidence that doesn't extend to some of the Balut's younger residents, who rebel against him and the Germans; somehow, he holds the Balut together longer than any of the other Polish ghettos. The general optimism was a fresh take, and I think was the reason the book is well-regarded - I enjoyed it for that reason, but couldn't escape the fact that it was obviously certainly fantasy, even if I wished it wasn't.I give it three sad things out of five.

Thursday, August 10

Finding George Orwell in Burma

The reason I mention my plight with the poo is because I think it relates to colonialism. Big fat cawing crows fly in from elsewhere and perch high above the citizenry. They then proceed to shit on the citizenry without pause. Once they have done all they can, they fly away home leaving a mess so great that efforts to clean it up are almost futile. Colonialism: The shit stain that won’t go away.

Anyway, my inane analogy aside, this is a fascinating little book. Writing under the assumed name of Emma Larkin (using her real name would spell doom for her friends in Burma and would make any return trips to the country quite dangerous) an American journalist based in Bangkok authored this peculiar combination travelogue and literary criticism. George Orwell's connection to Burmas was quite deep, he was born in colonial India, was stationed in Burma as a member of the Indian Imperial Police, later wrote a novel called Burmese Days about his experience in Burma, died in 1950 while in the process of writing a novella about “how a fresh-faced young man was irrevocably changed” after his time in Burma and, most importantly, modern-day Burma shares many characteristics with Orwell’s two most famous books, Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four.

There is an overwhelming Big Brother presence in Burma, and Larkin encounters people who are fearful of having conversations with her in teashops, concerned that an informant could be lurking. Larkin altered most of the names used in the book, even several of the locations, in an effort to the spare the well-being of those she spoke with. The newspapers feature a ridiculous collection of stories about government officials traveling to and fro while failing to mention practical matters like a fourfold increase in train fares. In an effort to conceal bad news the government makes all news hard to come by. Even the Buddhist monks are controlled by the government, and their large influence is used to help keep people in step with the police state’s policies. Burma is second only to Afghanistan in the amount of heroin it produces and this heroin is predictably used to deepen the pockets of government officials while the masses struggle.

The response of a Burmese man when asked by Larkin why the people appear so carefree despite the conditions within the oppressive police state: “Burma is like a women with cancer, he explained. She knows she is sick, but she carries on with her life as if nothing is wrong. She refuses to go to a doctor for treatment… She talks to people they talk to her. They know she has cancer and she knows she has cancer, but nobody says anything.”

Larkin does a good job of giving a feel for how tyrannical the Burmese government is but I wish she had delved a bit further into her analysis of Orwell’s writing. Too often her discussion of Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four seemed like an afterthought. She sprinkled the book with little ancillary tidbits that never go beyond a most basic understanding of Orwell’s writing. But I found the book in the travel literature section and travel literature it is. Pretty good, too.

Wednesday, August 9

Loopers, ahoy!

Meanwhile, I've been busy battling Tally Hall and LA sewage, so I have not been Looping lately. Rest assured that will be rectified, though I wither a bit in the shadow of the eloquent and verbose actual writers in the Loop. Inspiration, not intimidation, I must remember.

An old man told me, "Your days are for running, and your nights are for dancing until it is day."

Alright, Book-Loopers...

Fiction: Infinite Jest

I've read better novels than Infinite Jest, but the fact I finished the fucking thing makes me put it here: I still consider it an achievement. That said, it's a great novel, and I remember the details of it vividly even though I read it 8 years ago. It follows three stories concurrenly, if not temporally. The first is the story of young Hal Incandenza, a pot-addled teenager enrolled at the Enfield Tennis Academy in Boston, which is run by his mother, Avril, after the father's suicide. The second story is tha of ex-con Don Gately, who lives in a halfway house just down the hill from the Academy, and the third is a conversation between a wheelchair-bound assassin and somebody else on the American-Canadian border. Yep, it's a riot. On top of the 1100 pages of text, there are 100 pages of footnotes. This book is kind of like an acid trip in that I don't think I have the time and energy for it now, but I did back then, and I'm better for it. A really suberb experience.

Non-Fiction: The Power Broker

Quite simply the greatest book I have ever read. In recording the story of Robert Moses, New York's Parks Commissioner-turned-Czar, Robert Caro won a Pulitzer Prize and essentially wrote the post-Tammany Hall history of New York City. I would definitely say it helped to read the book while living in the city, just because every single part of the city, and how it was created, is discussed in the book, which like IJ is over 1000 pages. The amount of research is simply staggering, and it's baffling to think Caro wrote three (!) of these books on Lyndon Johnson, but that may be overkill. Maybe I'll get to them and like them more. But for now, this is the one.

Wild Card: Crappy Books

Yes, I could have gone with some Gabriel Garcia Marquez or some shit like that, but why? On occasion, I read crappy Robert Ludlum novels like The Prometheus Deception, which itself was a running joke between myself and BAG. While the plots of these books are standard (thirty-to-fourtysomething white hero, unnecessarily hot female along for the ride, predictable plot twist), it would be wrong to think you can't learn something by reading them. They're page-turners, which means they're almost uniformly well-written; they may be uninspired, but great ideas alone won't get you into Barnes and Noble. You need to keep people's attention, and I find I learn something about reading - which helps my writing - by tearing one of those books apart, and it only takes a couple hours. And there's guns and sex and stuff, which is fun.

Saturday, July 29

Robert Moses: The Original B-Boy

As I read Can't Stop Won't Stop I have found myself struck by how a movement that was so vital, so potent in its nascent stages, has now devolved into the current celebration of all things extravagant and dispensable. Certainly there are those who still pay homage to the roots of hip-hop in their own way, but these are a small minority when one considers who's getting airplay and who’s garnering platinum plaques. The great thing about a lot of popular hip-hop in the early days is that it was party music with a social message appended--Afrika Bambaataa's motto of "Peace, Love, Unity and Having Fun" really stood for something. Why is it that now it seems the songs must be one or the other, conscious or crunk? It’s really a shame, as it confines the power of the genre.

I’m making my way through Can't Stop Won't Stop incredibly slowly, which surprises me, I thought I would devour it. It’s a pretty dense book and I've been reading it in fits and starts, distracted by other books along the way. Although it is quite thorough and exceedingly well researched, Can't Stop Won't Stop somehow manages to be clear and concise, offering an insightfulness that--unfortunately--you wont find in some widely read hip-hop publications. If you’re curious about the history of hip-hop this is THE book. I'll likely comment on this book further as I make my way through it--especially when I get to the Native Tongues part.

Thursday, July 27

Facing the Congo:

A Modern-Day Journey into the Heart of Darkness

In some ways Tayler is the anti-Bryson, filling his prose with sober, severe language and almost never even cracking a smile. On the other hand, Bryson doesn't make trips that force him to be confronted with Mobutu's treacherous military men, the threat (real or imagined) of cannibals, or the dangerous desperation of otherwise decent people.

One wonders whether Tayler would have even made it safely from Brazzaville to his boat journey's starting point in Kinsangani had he not mysteriously won the admiration and assistance of one of Mobutu's colonels. The Colonel, a corrupt fellow like any other of Mobutu's officers, asks for nothing in exchange for providing Tayler with safe passage on his barge. It seems as though the Colonel is amused by Tayler's presence, not only because he is about to embark on an insane quest, but because he is a white man whose aim does not include the economic pillaging of the Congolese.

Though Tayler was not traveling along the Congo to exploit the riches of its natural resources, as I read the book I could not help but think there was still something rather off-putting about an American writer making this superfluous voyage through a country ravaged by colonialism, civil war, Mobutu, starvation, malaria and the continued crippling economic effects of the white world's exploitation. At one point during a particularly hopeless portion of the trip, Tayler acknowledges my concern: "I found myself stung by my failure and trying to deny what I would later come to see as obvious: that I had exploited Zaire as a playground on which to solve my own rich-boy existential dilemma."

Issues of propriety aside, the book is well written and contains several passages that rank amongst the most gripping I've ever read. I recommend this book, and not just to fans of travel literature. Tayler does a decent job of outlining some of the issues facing Zaire (now Democratic Republic of Congo) during the late 90's, but I think he falls short when he is so focused on the completion of his journey that he fails to develop a strong relationship with his African traveling partners. But, given the stress of his trip, it's hard to be too critical of the man's social skills, and perhaps I should only praise him for making it home alive--no matter how frivolous his journey was.

Tuesday, July 25

I live!

Thursday, July 20

Quoting Turgenev

"Weak people never put an end to things themselves—they always wait for the end."

"Weak people in their mental colloquies, eagerly make use of strong expressions."

Sunday, July 16

Recent Readings

I've since moved onto The Torrents of Spring by Ivan Turgenev. This book is, as the name of the author might imply, altogether different from Hemingway's Sherwood Anderson parody of the same name. It is curious to me that Hemingway would title his essentially American burlesque after a story by one of the Russian masters. If you have any information on this please do tell. Perhaps as I get a bit deeper I'll find some reasoning (it's quite a small book, so that could come momentarily), At any rate, Turgenev's Torrents is a pretty standard love tale. It's not written with the same elegance as Fathers and Sons but it's still quite good.

It's funny how I have come to read the two Torrents. When my father visited Seattle he saw that I had just read Fathers and Sons. He said the only Turgenev he had read was a wonderful love tale by the name of The Torrents of Spring. While touring the Seattle Public Library together he suggested we find it. We could not, but we did find the Hemingway work of the same name. We looked for the Turgenev at Elliot Bay Book Company here in Seattle and then at Powell's in Portland. No luck at either cavernous locale. Now, my father is getting on in years and I just assumed that he had confused one book with another--though mixing up Hemingway with Turgenev seems odd for a well-read being of any age or mental capacity. When my father left town I went back to the library and read Hemingway's Torrents just for kicks. It was fun, if dated. A few weeks ago when I visited home my father gave me a copy of Turgenev's Torrents that he had purchased for me. It seemed as though he had made it his mission get me the book after the initial failure in Seattle and Portland. Thoughtful man, my father.

My big brother gave me a crisp $100 bill for my birthday last week. I used the money to purchase seven books (he told me to buy music, but fuck him). Here is what I bought:

The Intuitionist by Colson Whitehead

Old School by Tobias Wolff

Snow Country by Yasunari Kawabata

Blindness by José Saramago

Ficciones by Jorge Luis Borges

The Elephant Vanishes by Haruki Murakami

The White Album by Joan Didion

Wednesday, July 12

We do have a fourth member

Nick Hornby on Freakonomics in the June/July issue of The Believer:

Freakonomics ocassionally hits you a little too hard over the head with a sense of its own ingenuity. "Now for another unlikely question: what did crack cocaine have in common with nylon stockings?" (One of the things they shared, apparently, is that they were both addictive, although stockings were only "practically" addictive, which might explain why there are comparatively few silk stocking-related drive-by shootings.) The answer to the question of whether mankind is innately and universally corrupt "may lie in... bagels." (The dots here do not represent an ellipsis, but a kind of trumpeting noise.) Schoolteachers are like sumo wrestlers, real estate agents are like Ku Klux Klan, and so on. I enjoyed the book, which is really a collection of statistical conjuring tricks, but I wasn't entirely sure of what it was about."

If Nick (not Hornby, our Nick) were here to speak for himself he would probably say that that last sentence summed up the telephone conversation between he and I regarding Freakonomics.

Monday, June 26

Garcia Marquez hometown holds vote to change name

ARACATACA, Colombia (Reuters) - The people of Aracataca, where Gabriel Garcia Marquez was born and first heard the ghost stories that would inform the "magical realism" of his novels, decide on Sunday whether to change the town's name to honor him.

A banner stretching across the road leading to this impoverished community in Colombia's northern banana-growing region already takes the new name for granted, saying "Welcome to the magical world of Macondo."

FULL STORY

Sadly, it was voted down.

Friday, June 23

De Sade and Dos

I read a book of interviews with film director Luis Buñuel. The topic of de Sade comes up again and again. At times it seemed as though the interviewers were steering the discussion down that path, but it is evident that de Sade’s work was well read within the 1930’s Spanish surrealist circle that Buñuel ran in.

Then I read an interview with philosopher Arnold Davidson in the May issue of The Believer. Davidson explains: “There were debates when the Marquis de Sade was arrested, for example, about whether he was wicked or suffered from a rare and hardly known mental disorder…. The category of sadism didn’t yet exist! So the Marquis de Sade couldn’t suffer from sadism, because it hadn’t been conceptualized as a possible disease category and his psychology wasn’t that of a sadist.”

Then there was some discussion of Marquis de Sade in either Playboy or Esquire, but I can’t locate it presently. I meant to write it down. So yeah, never had I given much consideration to de Sade, but now here he is, infiltrating my reading diet. This type of thing seems to happen to me a lot, but I am currently at a lose for other examples.

Now some more on Buñuel, because I can. Buñuel is what I would describe as a very literary film director. Perhaps an odd description for a surrealist, but I think it’s apt. In discussing his reasoning for making a film like The Phantom of Liberty, in which the viewer follows of a string of loosely connected vignettes with little central plot, Buñuel uses an example from Crime and Punishment. He says that Dostoyevsky’s classic did not interest him in the least, and that the story might have done better “…to follow Raskolnikov up the stairs, to see him pass a boy who is going out for some bread, to leave Raskolnikov and follow the boy, who becomes the main character in the subsequent episode.” We are to presume that from there in Buñuel’s re-working the boy might pass the story on to a young lady or street peddler or anyone that happened to catch his ineterest, and so on. It’s interesting.

I also enjoy this quote from Buñuel, a man of many obsessions: “I am not preoccupied by my obsessions. Why does grass grow in the garden? Because it is fertilized to do so.”

Side note: Buñuel, Dali and Lorca were close friends in college. That’s just seems too improbable to be true--these three artistic giants paling around the dormitories of Madrid.

Book-Loop isn’t really jumping off like I thought it would. I’m not sure what to post, but I wanted to post something.

Friday, June 16

So, I guess we can start now?

Two books I'm considering are:

Can't Stop Won't Stop

Easy Riders, Raging Bulls

How about let's kick things off with a most corny, yet enjoyable topic: Favorite Summer Reading.

Can't go wrong with Murakami. A Wild Sheep Chase and Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World stand out to me as particularly fun summer selections. Zora Neal Hurston's classic Their Eyes Were Watching God is set in the sultry deep South and is excellent reading for a languid summer's day. While the story doesn't necessarily make for light, summer fair the writing is so lovely that it is recommended for all seasons. One book I just completed that immediately joins my list is Joan Didion's Slouching Towards Bethlehem. It is a collection of some of Didion's best work from the early 1960's. A grab bag of extraordinary prose, it pretty much blew my mind. It is not too often that I dip into current pop-lit, but last summer I found Yann Martel's Life of Pi to be quite rewarding. Of course I must also include my favorite current author, David Mitchell. I highly recommend all four of his novels. Mitchell's best book, Cloud Atlas, could potentially be a little more of a mindfuck than you're willing to puruse with your summertime fiction, but you should definitely give it a try. Number9Dream and Black Swan Green are his easier, more straightforward reads. (Number9Dream might be best classified as Murakami-light). I suppose I should also add Raymond Carver, Michael Chabon, and The Believer Book of Writers Talking to Writers to round out my list.

Wednesday, June 14

Ideas On Book-Loop

Second, I think of this as a place to discuss books, recommend books, trash books, etc. We could even get a little Oprah shit going on, giving our seal of approval to books. But I'm not sure about swapping books - the hassle it takes to send them long distances, despite the coolness of the idea, is offset by the ease at which we could get them at the library.

Third, I'm trying to get some of my friends to sign up. The more the merrier, I guess.

I just finished The Deptford Trilogy, recommended to me by Ben, and I'm currently on The Tipping Point, which I'll be done with in no time. Then it's on to The Great Influenza, which I've heard great things about. And it's not in my profile below, but the greatest book I've ever read is The Power Broker by Robert Caro. It probably helps that I'm a New Yorker for that, but it is what it is.

Bryan

Between seeking a cure for the world's worst diseases, saving puppies from oncoming traffic and concurrently dating three of South America's most beautiful women, it's a wonder Bryan has time to read at all. When he turns the pages, though, he leaves this world entirely, and is better for it. He enrolled in the Enfield Tennis Academy in Enfield, MA, for an epic psychadelic journey through his teenage years; his 20s were spent roaming Tokyo, and roaming the recesses of his mind, after his bride left him; he later found a Colombian town where one strange and magical family dominated the town's history and activities for a century, and thereafter left for Buenos Aires, where he discovered a library without end, where he currently resides, looking for the one book that perfectly describes all others. He is friends with Ignatius J. Reilly, Robert Moses, and Magnus Eisengrim, and has read sadly of the fates that befell former chaps Humbert Humbert and Santiago Nasar. He'd love to share all he knows, and receive knowledge in return. In closing, Bryan is a man who also loves the outdoors, and bowling, and as a surfer explored the beaches of southern California from Redondo to Calabassos, and up to Pismo.

Between seeking a cure for the world's worst diseases, saving puppies from oncoming traffic and concurrently dating three of South America's most beautiful women, it's a wonder Bryan has time to read at all. When he turns the pages, though, he leaves this world entirely, and is better for it. He enrolled in the Enfield Tennis Academy in Enfield, MA, for an epic psychadelic journey through his teenage years; his 20s were spent roaming Tokyo, and roaming the recesses of his mind, after his bride left him; he later found a Colombian town where one strange and magical family dominated the town's history and activities for a century, and thereafter left for Buenos Aires, where he discovered a library without end, where he currently resides, looking for the one book that perfectly describes all others. He is friends with Ignatius J. Reilly, Robert Moses, and Magnus Eisengrim, and has read sadly of the fates that befell former chaps Humbert Humbert and Santiago Nasar. He'd love to share all he knows, and receive knowledge in return. In closing, Bryan is a man who also loves the outdoors, and bowling, and as a surfer explored the beaches of southern California from Redondo to Calabassos, and up to Pismo.

Thursday, June 8

A note for those joining us

This post will be like your profile on the site (check out Ben's for an example), and I believe that only you will be able to edit it, but please keep the title the same so we can maintain the link.

This is sort of a MavGyver'd way to create profiles, and I hope it will work long term. We'll see. Thanks, -Mike

Wednesday, June 7

Ben

Ben is a cagey veteran of the blogging game. Born and raised on the mean streets of Martha's Vineyard, where he studied under the masterful tutelage of Mr. Dodge, Ben went off to college in Michigan and graduated in 2003 with a BA in BS. He is currently studying abroad in Seattle, Washington. Ben's favorite writers include Saul Bellow, David Mitchell, Franz Kafka, Ernest Hemingway, and Robertson Davies. He feels as though he needs to broaden his horizons and read more work by female writers, as well as non-white dudes, but Ben is doing little to change his ways. He is currently reading fiction by a long-dead white dude, with an eye towards jumping into some more long-dead white dude fiction in the very near future. Ben's interests lie mostly in the realm of fiction, but he is not at all opposed to the idea of non-fiction.

Ben is a cagey veteran of the blogging game. Born and raised on the mean streets of Martha's Vineyard, where he studied under the masterful tutelage of Mr. Dodge, Ben went off to college in Michigan and graduated in 2003 with a BA in BS. He is currently studying abroad in Seattle, Washington. Ben's favorite writers include Saul Bellow, David Mitchell, Franz Kafka, Ernest Hemingway, and Robertson Davies. He feels as though he needs to broaden his horizons and read more work by female writers, as well as non-white dudes, but Ben is doing little to change his ways. He is currently reading fiction by a long-dead white dude, with an eye towards jumping into some more long-dead white dude fiction in the very near future. Ben's interests lie mostly in the realm of fiction, but he is not at all opposed to the idea of non-fiction.Favorite Books Read in 2008

The Braindead Megaphone, by George Saunders

Blue Highways, by William Least Heat-Moon

MJA

Mike, sporadic blogger and frequent loafer, was recently transplanted to Southern California. While working with the city of Los Angeles, he will spend his days longing for the intersection of S. State and Hoover and dreaming of the Brown Jug. He will be living alone and will read hungrily, in theory. Being a dork, Mike spends most of his time lately reading nonfiction, and his anticipated reading list is wanting for fiction to a large degree. He owns several classic books and has read maybe two of them. Mike would love to zip through some breezy summer fiction and tackle some classics in the very near future. His likes include chocolate, boobs, and free time. Dislikes include but are not limited to mint, fake boobs, and work.

Update II: Mike is pulling his head from the sand.

Update III: Head got sandy again. So, shaved head.

--------------------------------------------------------------

Reading:

The Brothers Karamazov, Fyodor Dostoevsky

--McSweeney's periodicals: Quarterly and The Believer, Various Authors

--Harper's

--Electronic Gaming Monthly

--SEED Magazine

--Discover Magazine

--Utne Reader

Loopy Library:

Fiction:

Crime and Punishment, Fyodor Dostoevsky

Slapstick, or Lonesome No More!, Kurt Vonnegut

The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck

A Farewell to Arms, Ernest Hemingway

For Whom the Bell Tolls, Ernest Hemingway

A Confederacy of Dunces, John Kennedy Toole

Everything is Illuminated, Jonathan Safran Foer

High Fidelity, Nick Hornsby

Bringing Out the Dead, Joe Connelly

Tandia, Bryce Courtenay

The Better of McSweeney's, Volume 1, Various Authors

Nonfiction:

What's the Matter with Kansas?, Thomas Frank

The Omnivore's Dilemma, Michael Pollan

Crossing the Rubicon: The Decline of the American Empire at the End of the Age of Oil, Michael C. Ruppert

Natural Capitalism, Paul Hawken, et al.

European Dictatorships 1918-1945, Stephen J. Lee

What's the Matter with Kansas?, Thomas Frank

Storm of Steel, Ernst Junger

Stalinism as a Way of Life, Lewis Siegelbaum and Andrei Sokolov

Nazism and German Society 1933-1945, David F. Crew

Peoples and Empires, Anthony Pagden

Where I Was From, Joan Didion

A Man Without a Country, Kurt Vonnegut

The God Delusion, Richard Dawkins

The Outbreak of World War I, Holger H. Herwig

Earth in the Balance, Al Gore

Domicile:

Michael Affeldt

2723 Vanderbilt Ln., Apt. 16

Redondo Beach, CA 90278

Tuesday, June 6

Gotta start somewhere...

If it were based around a website, I would call it BookLoop.com or something like that. Note: I just checked that domain and it said, 'future home of book loop.'

So people could sign up and list all the books they had that they were willing to share with others, with the possibility of not getting them back. They would in turn list books they would like to find from other people. The website could match the requests and give the sender shipping instructions. Maybe you would earn a credit for each book you sent, which you then could spend to get one sent to you. Maybe you could use multiple credits to get more highly-requested books. Participants would be encouraged to make notes and such in the margins to foster a sense of community in the BookLoop users. In addition, the website could be a base for discussion, debate, reviews, recommendations, whatever."

- MJA, June 5, 2006